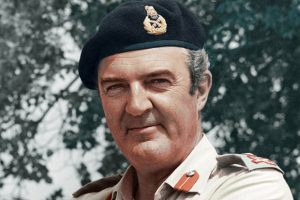

We are sorry to have to report that Major General Mike Reynolds (East 1947) died on October 21 at the age of 85.

We are sorry to have to report that Major General Mike Reynolds (East 1947) died on October 21 at the age of 85.

Mike came to Cranleigh in 1944 and recounted his three-year in some detail in his autobiography, from having his bowler hat kicked around the houseroom on his first day to the day the boys staged a short-term rebellion against being served tripe.

A full obituary appeared in The Times on November 12.

Mike Reynolds turned to authorship after his battlefield tour coach became stuck in a Belgian lane in the midst of a downpour. Exasperated that he would be unable to explain the Ardennes campaign to his audience, he decided on writing rather than talking about military history. He concentrated initially on Britain’s erstwhile enemies, beginning with a sinister and controversial one.

In The Devil’s Adjutant (1995) he told the story of Jochen Peiper, the commander of the SS Kampfgruppe responsible for the massacre of US Army prisoners at Malmédy in Belgium and other crimes. Resolved on making an objective analysis, Reynolds explored Peiper’s boyhood attraction to the Nazi party, his success as a Panzer leader, his trial for war crimes and finally his murder by former members of the French Resistance in France in 1976. Portraying a convicted war criminal as an outstanding soldier was decidedly risky but Reynolds’ meticulous research and objective presentation defused any controversy. It was a highly successful book for a hitherto unknown author, selling more than 30,000 copies.

Encouraged, he wrote three more books about the Schutzstaffel (SS) literally “defence echelon” or Führer’s bodyguard: Steel Inferno (1997), Men of Steel (1999) and Sons of the Reich (2002). All did moderately well but did not match the sales of The Devil’s Adjutant.

He then embarked on controversy of a different kind to produce Monty and Patton: Two Paths to Victory published in 2005. The mutual dislike shared by Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery and General George S Patton was common currency during the latter half of the Second World War — the two commanders having diametrically opposed philosophies on war. Montgomery demanded thorough planning, overwhelming fire support and logistic back-up, while Patton chanced his arm, dashed forward when military logic suggested he should pause, and fought on a logistic shoestring. Both men won their key battles and their starkly different methods still merit study.

Michael Frank Reynolds was born in 1930 in Birmingham to Frank and Gwendolen (née Griffiths). His father worked for Barclays Bank and his mother stayed at home. As a boy, he witnessed the crash of an RAF aircraft in 1943 and, with his father, found the remains of the body of one of the crew as the smoke cleared from the debris. He won a scholarship to Cranleigh and his interest in military matters led him to apply for Sandhurst during National Service.

He had the determination and sense of humour essential to endure the strains of army life. Yet his military career almost ended when it had barely begun. Seriously wounded in the leg in Korea, amputation threatened. Through sheer resolve not to be downgraded — and against all medical predictions — he regained fitness but with his right leg shorter than his left.

Commissioned into the Queen’s Royal Regiment in 1950, he had been sent as an officer reinforcement to 1st Battalion The Royal Norfolk Regiment in Korea, where the front had stalled along the 38th parallel. When he realised that he was usually the one selected to take a patrol into no man’s land or ambush the enemy, he wondered if it was because he came from a different regiment. In fact it was because he was the best man for the job.

On the night of August 2, 1951, he took an ambush party out to wait for an enemy move forward. He had just deployed his three fire sections when one was attacked in strength by Chinese infantry, firing furiously. Grenade fragments struck him in the face and leg, leaving him just able to crawl. His orderly, Private Bob Ketteringham, was shot dead trying to carry him to safety. After lying in the open for nine hours, he was recovered soon after dawn. Six weeks later he was lying in Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot, awaiting a verdict on his leg from a senior surgeon. “We’ll have that off on Thursday,” said the great man. Using a carefully built-up shoe, Reynolds walked and eventually ran until he was fit to return to duty. Immediately on leaving hospital he visited Bob Ketteringham’s parents to tell them how their son had died. After hearing the story his father remarked, “Well, that’s the just sort of thing Bob would have done, isn’t it.”

While on leave on crutches at a Birmingham cocktail party, he was noticed by Miss Anne Truman, who walked over to ask how he had been injured. A few months later, Reynolds proposed, converted to her Catholic faith and they were married at Birmingham Oratory in 1955. They had three daughters in a long and happy marriage: Victoria, who became a matron at Charterhouse School; Gabrielle, a designer in her husband’s family wool business; and Deborah an art historian.

Reynolds acquired many friends of all ranks on his way up to command of a battalion. He took 2nd Queen’s on an emergency tour of duty to Londonderry where they did well during the worst of the Troubles, but he received no recognition for it. His habit of good humoured questioning of instructions he judged unnecessary — or even absurd — did him no lasting harm. He was appointed to command the 12th Mechanized Brigade in Germany at the end of 1974 and in 1980 Reynolds took over Nato’s Allied Command Europe Mobile Force (Land) with the rank of major-general near Heidelberg.

His camaraderie and approach to international friendship fitted him ideally to this job. At the end of his tenure in 1983 he was told he was to go to Brussels as the senior British officer on Nato’s International Military staff (IMS). On protesting that he would prefer to serve in England where he could find a house and a civilian job, he was confidentially advised that it was hoped he would be the next head of the international military staff as a lieutenant-general. So he accepted the two-star job, only for the top post to go to a Belgian Air Force officer when the time came.

His last book, in 2013, was a light-hearted autobiography, Soldier at Heart: from Private to General. He dedicated it to Private Bob Ketteringham who had come to his aid in Korea.