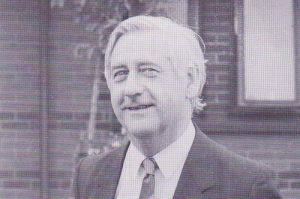

We are sorry to report that Ken Wills, who taught physics at Cranleigh between 1949 and 1988, died on August 19 after a short illness.

Ken was second master to Marc van Hasselt and then Tony Hart between 1974 and 1988, and before that was housemaster of 1 North from 1959 to 1974.

The following article, written by the then headmaster Tony Hart, appeared in the Cranleighan in 1988 on the occasion of Ken’s retirement.

I have asked myself the question: “At the end of thirty-nine years at Cranleigh School, what would Ken Wills most wish to be remembered for?”. Certainly it would not be for the successful apprehension of any number of minor (and some serious) offenders against the School Conventions during his 14 years as Second Master. That gave him little pleasure and some pain.

Rather, I think it would be (as he hinted this year in his address on Speech Day) for his consistent pursuit of academic excellence, and for innovation in the business of schoolmastering. When he came to Cranleigh in 1949 — and I hope I tread on only a few toes — it was a far less academic school than it is now. Much of that progress stems from his efforts — in designing an unusually complex and broadly based timetable, which for many years virtually avoided “subject options”; in his support for Nuffield Science (and his insistence that anything other than three separate sciences was simply not respectable); through his advice on academic appointments; through his influence on the Housemasters’ and Academic Committees; through his control, even, of the prize list for Speech Day, where the sole criterion, he always insisted, should be academic excellence.

He was an innovator, too, in the pastoral side of schoolmastering. As a Housemaster he was among the first to abandon corporal punishment and deeply regretted in later years that he had ever had anything to do with it. The 1 North House Rule Book was effectively scrapped on his appointment and replaced by a simple code of conduct and good behaviour. He was a fervent advocate of girls in the Cranleigh Sixth Form and delighted in Nan, his wife’s, wish to have a career of her own at a time when that was not a fashionable thing to do. (And how Cranleigh has benefited from her skills and talents in so many drama productions.) The abolition of fagging also gave him great pleasure and as Second Master he always resisted any hint of its resurgence in other guises, however trivial. He encouraged the gradual abolition of the myriad petty tyrannies and restrictions which so dominated school life in earlier years. Studies in place of dormitories, Exeats, a more balanced view of the place of sport: all were new in their day and all had his support over the years. Above all, he set values before rules and the essential before the peripheral. If Cranleigh is a saner, happier and more humane place in the 1980s, it has much to do with Ken Wills ;s robust and enlightened liberalism.

That robustness is one of the many qualities which made him such a great schoolmaster. A limp or woolly liberal would have achieved little, however radical his own opinions. There is about Ken a crisp decisiveness, a lack of nonsense and a powerful contempt for cant or humbug. He knows how to turn ideas into action and he can identity the men who will carry things though. “Soggy” is perhaps his ultimate condemnation. His energy is phenomenal. a restless, electric outpouring which galvanises those around him, (he will probably correct my physics). It was. I think. Nan who once pointed out to me that when Ken comes to dinner, his feet always scuff the carpet under his chair: he never stops moving.

Ken never pretended to know the names and faces of every pupil in the School — why should he? — but he knew well all those he had taught, all who had been in his House, all with whom he had had any particular dealings. Above all he had a deep and intuitive under-standing of the species “boy” and its behavioural patterns. Take one evening in 1985 when two boys had gone missing with a bottle of spirits, he said, most fortunately for them as it happened: ‘They will either be behind the Pavilion or they will be on the old railway track.” It turned out to be the latter. So often it was like that. There were very few things which Ken had not seen before; and yet he retained a grudging admiration for the perennial ability of the young to surprise us with something new and outlandish.

Few Second Masters can have enjoyed less the disciplinary role which goes with the post. Because he was sensitive he could be hurt. Without being sensitive he could not have done the job. He did it because he was asked to. He did it thoroughly and fairly, never reaching a conclusion without a painstaking search for evidence, of which any police inspector would have been proud. But he always disliked playing the policeman, seeing it as an intrusion into a better relationship based on mutual trust, confidence and good-humour. The role suppressed his sense of fun and distanced him from the young. It was a job to he done but it gave him little joy; and again and again, having identified an offender, he would argue for clemency and understanding of the teenage condition. “Always remember”, he once told me. “they want to he treated like adults and forgiven like children.”

There was, perhaps, a side of him which Cranleighans who knew KSG only as Second Master — and particularly if they had crossed his path — never appreciated until after they left. Then, in a different and more equal relationship, they saw, possibly for the first time, that twinkle in the eye (so well caught in Peter McNiven’s portrait of him), that irrepressible good humour, the kindness and the humanity. That, of course, was the real Inspector Wills.

I have often wondered what he made of my own arrival, though I never asked: the ultimate in professional schoolmasters, after 35 years faced with his sixth headmaster and one who had never been a schoolmaster before. And yet, perhaps it was consistent with his general philosophy that Cranleigh would flourish by being different, by bucking trends, by doing the things that were not obvious. Whatever he thought. the loyalty was unswerving, he saved me from a thousand mistakes and for four years we worked together without a cross word. For me it was a continuous tutorial, in which I absorbed from an expert the lessons of a lifetime and some of the instincts — the ability to say with some hope of bring correct: “That boy does not look right today. Something’s up”.

There were so many pleasures in working with Ken. He writes the most wonderful English trenchant, clear and elegant with the clarity of expression that conies only from clarity of thought, as with so many of the best scientists. There was, too, that rapier wit without which our business meetings will not he quite the same again. “If you take that boy, we will be depriving some Sussex village of its idiot”, which might sound unkind, but somehow was not when he said it. There poured from him daily a flow of such epigrams which we began to collect. “All Sixth Form magazines walk a narrow line between being funny and being banned,” or again “In order for a tutorial to be successful, both parties should at least be present.” and “There’s no such thing as a friend in the motor trade.” Through it all, there was that vitality and sense of Kan which he and Nan bring to their lives — their kindness and hospitality, too, to so many of us who have been entertained in their home and whose worries and burdens they have shouldered.

An OC from some years hack once came to see me about sending his son to the School and asked to he remembered to Ken. Unfortunately, in passing on the message I could not quite recall his name. “Never mind.” said the Second Master, “all OCs of child-bearing age know me.” It would be tempting to comment that that says it all: in a career extending over almost one-third of the life of the School, the man had become a legend and an institution. But of course it does not say it all, for it is the quality of the recollection which counts. ,As Ken and Nan retire to their new home on the edge of the Sussex Downs — which he is already busy rewiring — they can he happy in the knowledge that they will he remembered by hundreds of us with something much more than ordinary affection.

Tony Hart