A number of comparisons are being made between the current coronavirus pandemic and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. Both caused a massive disruption to life across the world (although during the early stages of the Spanish Flu the First World War rumbled on) and on a local level both caused the premature closure of the School. But perhaps one of the most significant differences was that Spanish Flu impacted on the young far more, with the majority of victims being in their 20s or 30s.

As the country celebrated the Armistice on November 11 1918, all was quiet at Cranleigh where the boys had been sent home after the School was overwhelmed by Spanish Flu. The Cranleighan noted that “one small boy remarked there might have been a half-holiday, had it not been for the flu … whereas, of course, as it was, he only had a fortnight’s holiday at home”.

The School was lucky in that there were no fatalities but in Britain overall there were 228,000 deaths, and globally it is estimated as many as 100 million may have perished.

The first wave of Spanish Flu had first been noted in the trenches in the spring where it was known as la grippe (influenza). Initially not serious, it quickly started taking a toll. The first Cranleigh casualty was Sergeant Cecil Bate (1&4 South 1907) of the RAF who died in Lilliers, France on July 10.

The second wave, which arrived in the autumn, was catastrophic. It is thought the virus had mutated and it swept through a population already weakened by four years of war. In early October 1918 the Surrey Advertiser carried a headline “‘Influenza in Surrey: A Widespread Epidemic”. The article said: “So far, there have been comparatively few deaths among the civil population, but in the camps, it is a different matter … there are victims by their hundreds.”

A doctor wrote to the British Medical Journal explaining the infection. “It starts with what appears to be an ordinary attack of la grippe. When brought to the hospital, [patients] very rapidly develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission, they have mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis [blueness due to lack of oxygen] extending from their ears and spreading all over the face. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible.”

On October 8 Trooper Arthur Lindridge (East 1903) of the Guards Machine Gun Regiment died in France. He had joined up a fortnight after war was declared in 1914 and served in France since 1915. He was 29. Ten days later Henry Casswell, one of the first pupils who arrived in 1866 and a master from 1870 to 1894, died from influenza at his home in Rusper.

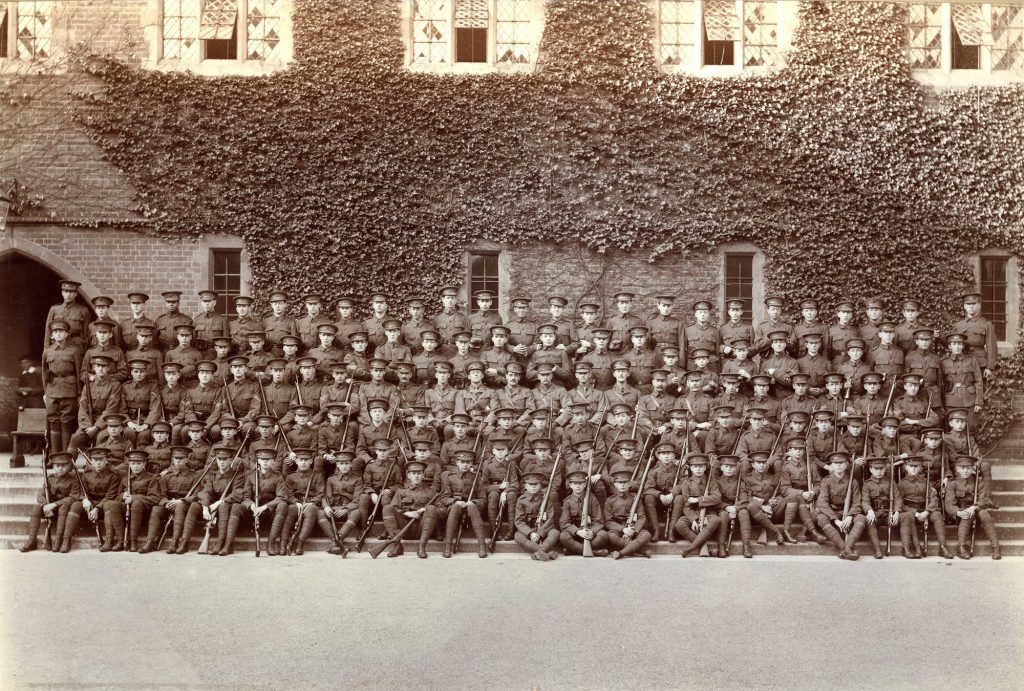

Influenza reached the School in late October. West house, as was the norm as it was closest to the kitchens, was immediately converted into a San overflow (the house was temporarily relocated to the gym) but within a day or two that too was overwhelmed, as were 1 and then 2 North which were also commandeered as emergency sick bays. “The attack came with great suddenness, and within a few days some 260 boys were in bed,” the Cranleighan said. “The disease fell with equal rigour on the masters and the staff of servants, most of whom were caught by the plague.” At its height, only 30 boys and a handful of staff were unaffected.

Parents and friends who lived locally offered help, which was readily accepted, and, as was usual when large-scale sickness hit, extra nurses were drafted in, but despite this the School could barely function. The Headmaster had no choice but to close the School and telegrams were sent to all parents that boys would be sent home for a fortnight. Those unaffected were sent home by train immediately, others followed after recovering (“happily the type of influenza was mild, and most of those who suffered were in a few days able to get up”). A few who lived far away were billeted with masters or friends. The break worked in that the illness was contained.

The Prep School was largely unaffected. It, rather flippantly, dismissed the illness in one short paragraph in the school magazine. “The epidemic tried hard to get in here, in fact, it caught Mr. Norman when he was not looking, just fluttered over the boys, and was then driven out by a liberal use of quinine and fresh air. Several boys went home in a fright, but recovered their equanimity within a week.”

On the Western Front, influenza continued to take a toll. On November 9, 23-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Len Thornback (1&4 South 1911) of the RNVR died. Like Lindridge, he had served throughout the war.

When the third wave of influenza hit in the New Year, the School was largely unaffected as, generally, those who had recovered from it had immunity. Although West house was again turned into a sick bay, the illness was contained. However, in the Village there were fatalities, perhaps none as tragic as the three Gamblin brothers – John (18), William (27) and Henry (25) – who died within three days of each other in March 1919. Two other Gamblin brothers had already been killed in the war.

Another three Cranleighans on military service perished from influenza in that third wave. On February 20 1919 Lieutenant Charles Hobson (1N 1899) died while serving in Ireland. On February 21, Lieutenant Sidney Kemp (West 1917) of the RAF died at Etaples. He had just turned 19. A day later 34-year-old Private William Newton (East 1900) of the Army Ordnance Corps also died.