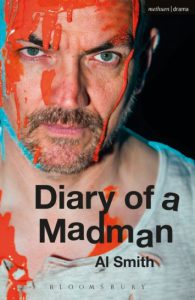

Writer Al Smith (2&3 South, 1995-2000) has won critical acclaim for his new play Diary of a Madman which transferred to London’s Gate Theatre in Notting Hill from the Edinburgh Festival.

Writer Al Smith (2&3 South, 1995-2000) has won critical acclaim for his new play Diary of a Madman which transferred to London’s Gate Theatre in Notting Hill from the Edinburgh Festival.

The Times review said that “no other play that takes on the themes of our own brave new dysfunctional world so successfully…. this is a funny, sad, smart, acutely drawn … [it] is an authentic story of our time” while The Daily Telegraph said: “It’s the most potentially contentious play I’ve seen in ages, yet heads condemnation off at the pass by drawing this frothing patriotic archetype with rare sensitivity and empathy.”

Smith said Diary of a Madman was “based, rather loosely, upon the short story of the same name by Nikolai Gogol. His short story follows the life of Poprischin, a lowly civil servant trapped in the wheels of the 1830s Russian bureaucracy. Bored, lonely and frustrated by his position in society, Poprischin writes about his life in 20 ever-increasingly bizarre diary entries. Though it is unclear to him, by the time he starts to detail his conversations with talking dogs its clear he is rattling headlong towards a schizophrenic episode fuelled by rank-obsessed impotence and an unrequited love for his boss’s daughter. As he details in his last diary entry the story finishes with Gogol’s hero descending into a manic frame of mind where he believes himself to be the unrecognised King of Spain.

“When asked to adapt it I felt in two minds; on the one hand I didn’t find myself particularly engaged by the time period or Gogol’s funny but awkward tone, yet on the other I found myself drawn towards the way his hero’s psychosis is reflected in a formally fascinating structure. I wondered whether there was a way of starting a play entirely naturalistically and then gradually warping its narrative into something unhinged without the audience fully recognising the changes of gear. In that sense I wanted to pinch more of Gogol’s structure than his plot. What I needed was a new mirroring story to reflect my version off. I didn’t have to look far.

“Shortly after leaving Cranleigh I got a summer job as a set-builder at the National Youth Theatre. There, I fell for a girl from South Queensferry, a town just outside Edinburgh. When the summer ended I was offered a place at Edinburgh University and, unsure quite what to do with my life I accepted the place partly for the city and partly for the girl. As I got to know her I’d spend more and more time with her family in South Queensferry, a beautiful place in the shadow of the Forth Rail Bridge.

“Though I felt like a fish out of water her family were extremely kind to me and made me feel enormously welcome. They were terrifically warm-hearted generous people, keen to give me, an English outsider, as much stick as they fancied. But for all their light-heartedness they were also a family overshadowed by a tricky mental health issue. Both father and brother suffered from schizophrenia, a condition that would, from time to time, draw them out of control of their lives. It is a brutal illness, one that robs people of their autonomy and subjects its sufferers to often long-term medication use. I was particularly moved by the care her family took of each other and by the grace with which they bore their difficulties. When the time came to submit my take on the short story I asked my old friend whether she would mind if I stitched together the Gogol with my experience of living with her family. She was understandably a little hesitant but gave me her blessing.

My version of Diary of a Madman is deeply rooted in that experience. It tells the story of Pop Sheeran, a painter charged with the Sisyphean challenge of painting the Forth Rail Bridge (in legend it takes a year to paint and needs to be repainted yearly). When a young English chemical engineering student arrives for his summer apprenticeship on the bridge with a new kind of long-lasting paint, Pop realises that he’s literally painting himself out of a job. And when that Englishman starts a relationship with his daughter, Pop’s hold on reality starts to become unstitched.

“I was nervous when my old friend came to see the play. Though I’d worked extremely hard to be even-handed and true to our experience it must have been hard for her to see that period of her life reflected on stage. I was deeply relieved when she said she was moved by it, and that she’d enjoyed it. And though we got great notices, in my mind, when the roots are real, there’s no greater critic than her.”